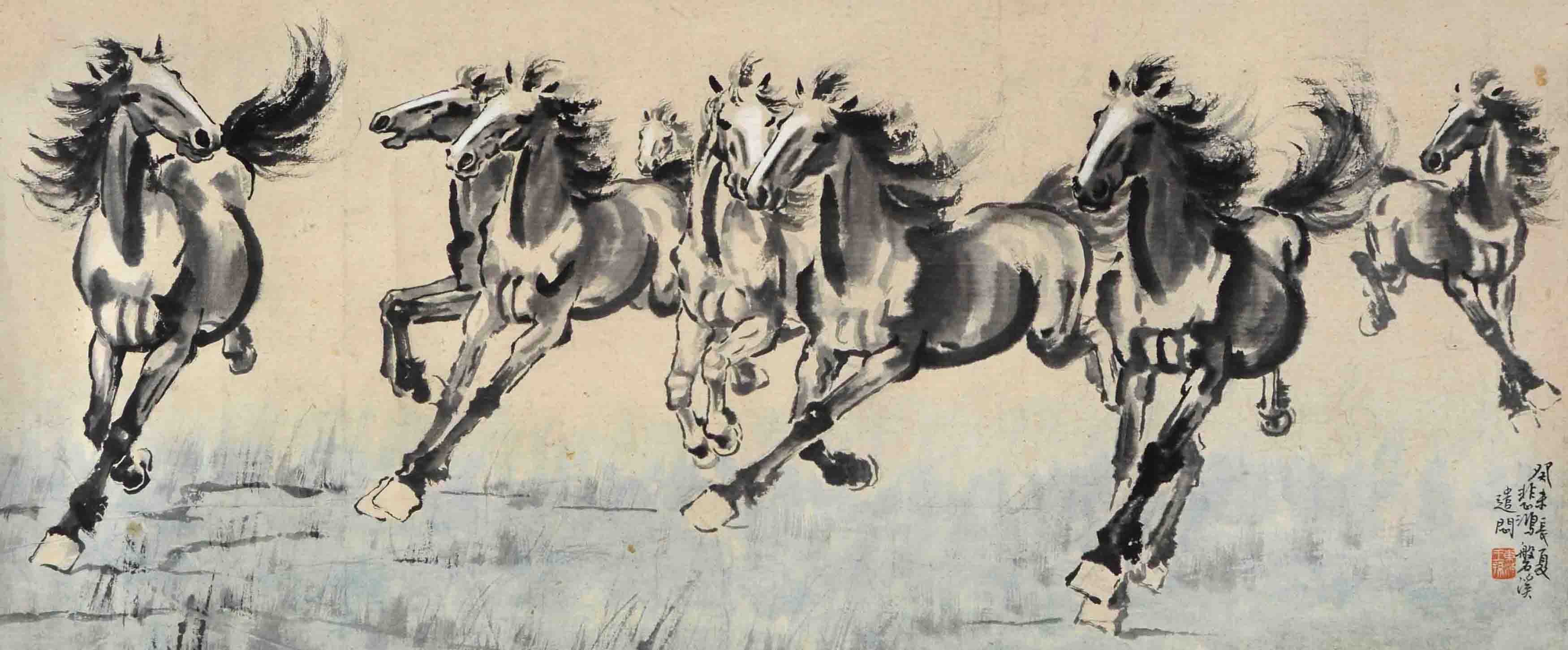

Who wouldn’t want to be compared to a stallion? They embody the perfect combination of power and beauty. But anyone who knows the first thing about horses realizes the differences between the strength and elegance of a wild stallion verses the strength and elegance that comes from a stallion and its rider. Indeed, there are higher levels of strength and beauty that come from a trained stallion that is focused in a particular direction than that which is found within those left to the wild herd. But even among the trained stallions there are different levels of horses. As zen master Shunryu Suzuki paraphrases a story from within his tradition:

It is said that there are four kinds of horses: excellent ones, good ones, poor ones, and bad ones. The best horse will run slow and fast, right and left, at the driver’s will, before it sees the shadow of the whip; the second best will run as well as the first one does, just before the whip reaches its skin; the third one will run when it feels pain on its body; the fourth will run after the pain penetrates to the marrow of its bones. You can imagine how difficult it is for the fourth one to learn how to run!

When we hear this story, almost all of us want to be the best horse.

The first several times I read this text I thought to myself, of course I want to be the first horse! I especially want to be like the first horse when I am feeling more like the second and third horses. And, of course, there are the days when I feel like the fourth horse and I think to myself, “how difficult it is…to learn how to run!” I want to run the course of my everyday life with the liberty and ease of the first horse but the only thing that seems to motivate me is some sort of pain. How many areas of my life do I need the whip? How often is the threat of pain our primary motivating factor? We procrastinate because the pain of repercussion is too far away. The whip is out of sight, out of mind. Or sometimes we might not do an excellent job at something because we are satisfied with discomfort of mediocrity. The pain of the whip is not greater than the comfort of mediocrity. In those instances, the only thing that can move us out of our general malaise is when the pain penetrates to the marrow of our souls. For some of us, this realization is repulsing. But what are we to do? Are we to bring back the ancient practice of self-flagellation?

But as I read the description of the four horses more closely, I realized the significance of the “driver’s will.” Who is the driver? At first I assumed that I was the driver. The problem was that I could not do what I willed to do, as depicted in the classic Romans 7 text, “I can will what is right, but I cannot do it.” But then I realized that the will of the horse and the will of the driver are two separate wills. And the strength and freedom of the first horse is because his will is unified with the driver’s will. It does not need the threat of pain, or even the shadow of the whip, to run a certain way or in a certain direction, because its will and the driver’s are one. When pain is the motivating factor for any sort of action, then that is the sign of a lack of union of wills.

A Holy-Spirit-filled life is one that is marked by freedom and power, and an absolute union of wills. A union of wills does not necessarily mean one will dominating the other. We often assume that when we surrender our will to the Holy Spirit that we are extinguishing or suppressing all that makes us who we are in order to be dominated by the will of the Spirit. However, God does not want to dominate us.

A friend of mine once had two horses: one was a bit shorter, but strong; the other taller, and loved to run. There were times when I wanted to take a horse exploring in the woods, and there were other times when I wanted to race through meadows and over hills. Obviously, I would choose the shorter one that could walk slowly up hills in thick woods over the taller one. And I would choose the taller one that loved to run when I wanted to race over the hills. While I was the “driver,” my desire was to take the horses to places that suited their nature. In the same way, when we submit to the guidance of the Holy Spirit, we are not denying our true nature but trusting that the will of the driver knows where to lead us so that our true nature can truly run.

As the psalmist says in Psalm 32

8 I will instruct you and teach you the way you should go;

I will counsel you with my eye upon you.

9 Do not be like a horse or a mule, without understanding,

whose temper must be curbed with bit and bridle,

else it will not stay near you.

This is where true life and liberty is found, in the nearness to God. Ultimately we do not desire nearness to God in order to obtain power and freedom. The nearness to God is the ultimate end in and of itself. Freedom and power are sings and byproducts of that nearness, but that is not what we desire. God does not desire to be near to us because of something we can give God, nor should we desire to be near to God because of something God can give to us. God also does not want us to stay near to Him by tethering us with a bond of slavery. Rather, God wants our bonds to be tied by a mutual cord of longing. This is why the prayer in the Cloud of Unknowing says, “rope us with a leash of longing.”

In Suzuki’s commentary, he mentions that if you think the goal is to train you to become one of the best horses, you will have a big problem.

“If you study calligraphy you will find that those who are not so clever usually become the best calligraphers. Those who are very clever with their hands often encounter great difficulty after they have reached a certain stage…we say, ‘A good father is not a good father.’ Do you understand? One who thinks he is a good father is not a good father; one who thinks he is a good husband is not a good husband. One who thinks he is one of the worst husbands may be a good one if he is always trying to be a good husband with a single-hearted effort.”

In other words, the goal it is not being a good horse or a good calligrapher or a good husband, but longing with a “single-hearted” desire to be good. As Christians, this is essential because we cannot arrive at a state of true excellence in and of ourselves. Furthermore, we should not desire that sort of excellence, as if it actually exists. Rather, our excellence is contingent upon our unity with God the Father through Christ the Son, bond together in love by the Holy Spirit. The most important thing to desire is the desire itself to be one with God. This can only be realized when we reach a true purity of heart. As Kierkegaard says, purity of heart is to will one thing. How often to we desire the byproducts of union with God more than we desire the actual union. True excellence and purity of heart is to desire the union of wills with God a single-hearted desire. The first horse is excellent not because he wants to be excellent, but because he wants to be one with the driver. We to will become excellent when we no longer desire excellence more than we desire God.